If you’ve ever opened a CSV and immediately regretted it, welcome to the club.

Most “real” datasets don’t show up in a neat little table with perfect headers and consistent values. They show up with mixed date formats, weird nulls, duplicated rows, and numbers stored as strings because someone exported it from somewhere that hates you.

This post is my practical, repeatable way to clean a messy dataset using Python + pandas without turning the notebook into an unreadable crime scene. The goal is not “pretty code.” The goal is trustworthy data.

The Dataset I’m Pretending You Got From Someone’s Email

Let’s say you received a file named transactions.csv. It’s supposed to represent purchases, but it has issues like:

- Dates stored in multiple formats

- Amounts with dollar signs and commas

- Duplicate transaction rows

- Missing or inconsistent categories

- Surprise whitespace everywhere

Here’s a realistic starting point.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv("transactions.csv")

df.head()Before touching anything, I do one thing: I inspect.

df.info()

df.describe(include="all")

df.isna().mean().sort_values(ascending=False).head(10)This tells me:

- Which columns are actually numeric vs “object pretending to be numeric”

- How bad missing data is

- Where I should focus first

Step 1: Standardize Column Names (You’ll Thank Yourself Later)

Column names are always inconsistent. Standardize early.

df.columns = (

df.columns

.str.strip()

.str.lower()

.str.replace(" ", "_")

.str.replace(r"[^a-z0-9_]", "", regex=True)

)Now every column is easier to reference, and your future self stops hating your past self.

Step 2: Clean Strings Like a Professional (Not Like a “Quick Fix”)

Whitespace and casing issues break joins, filters, and groupies.

string_cols = df.select_dtypes(include="object").columns

df[string_cols] = df[string_cols].apply(lambda s: s.str.strip())For specific columns where casing matters:

df["category"] = df["category"].str.lower()

df["merchant"] = df["merchant"].str.title() # nice for displayStep 3: Convert Money Columns The Right Way

If amount looks like "$1,204.33" you can’t do math until you fix it.

df["amount"] = (

df["amount"]

.astype(str)

.str.replace(r"[\$,]", "", regex=True)

.str.replace(r"\((.*)\)", r"-\1", regex=True) # handle (123.45) negatives

)

df["amount"] = pd.to_numeric(df["amount"], errors="coerce")Now you can do real analysis without silent errors.

Step 4: Parse Dates Like You Don’t Trust Anybody

Dates are messy. Be defensive.

df["transaction_date"] = pd.to_datetime(

df["transaction_date"],

errors="coerce",

infer_datetime_format=True

)Then check how many failed:

bad_dates = df["transaction_date"].isna().mean()

print(f"Bad date rate: {bad_dates:.2%}")If bad date rate is high, that’s not a pandas problem. That’s a “source data needs help” problem.

Step 5: Remove Duplicates, But Prove You’re Removing the Right Ones

I don’t just drop_duplicates() blindly. I define what makes something “the same.”

Example: treat duplicates as same user_id + transaction_date + amount + merchant.

key_cols = ["user_id", "transaction_date", "amount", "merchant"]

before = len(df)

df = df.drop_duplicates(subset=key_cols, keep="first")

after = len(df)

print(f"Removed {before - after:,} duplicate rows")If you’re in a job setting, that print statement becomes a data quality metric you can report.

Step 6: Fill Categories Intelligently (Not Randomly)

You could fill missing categories with "unknown", but that’s lazy and usually not helpful.

Instead, I’ll fill missing categories using the most common category per merchant.

merchant_to_cat = (

df.dropna(subset=["category"])

.groupby("merchant")["category"]

.agg(lambda x: x.value_counts().index[0])

)

df["category"] = df["category"].fillna(df["merchant"].map(merchant_to_cat))

df["category"] = df["category"].fillna("unknown")This is one of those “small things” that makes your dataset feel dramatically more usable.

Step 7: Add a Few “Quality Checks” That Catch Real Issues

If a pipeline produces data, it should also produce confidence.

Here are quick checks I use constantly:

1. Validate that amount isn’t insane

df.query("amount > 100000 or amount < -100000")[["user_id", "merchant", "amount"]].head()2. Ensure key fields aren’t missing

required = ["user_id", "transaction_date", "amount"]

missing_required = df[required].isna().mean()

print(missing_required)3. Make sure dates aren’t in the future (usually)

df[df["transaction_date"] > pd.Timestamp.today()].head()Step 8: Produce an Output That’s Actually Useful

After cleaning, I want:

- A clean file (parquet if possible)

- A basic summary that confirms things look right

df.to_parquet("transactions_clean.parquet", index=False)

summary = (

df.groupby("category")["amount"]

.agg(["count", "sum", "mean"])

.sort_values("sum", ascending=False)

)

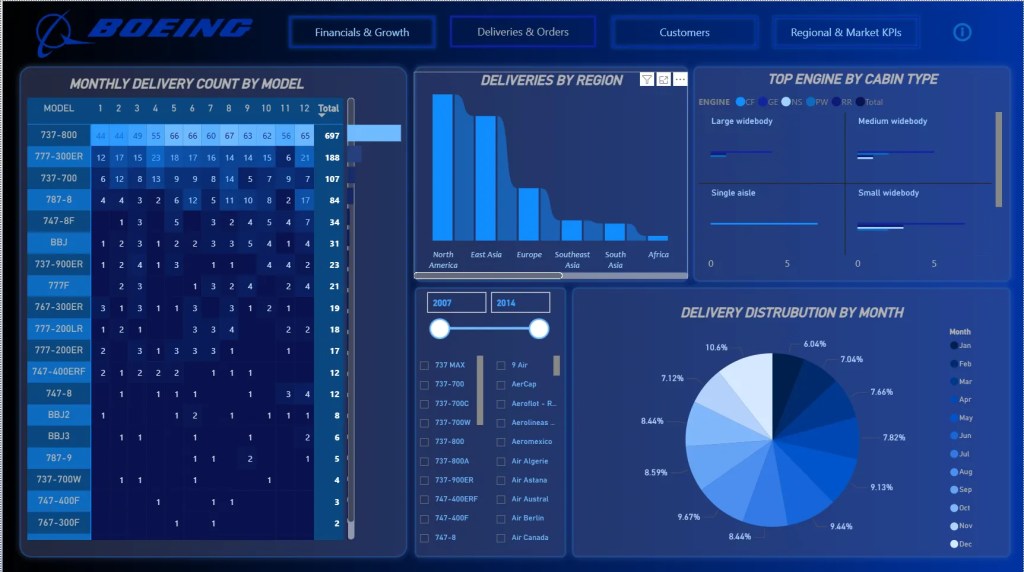

summary.head(10)That summary table becomes the first slide in a “here’s what I found” update, or the start of a dashboard.

Why This Matters (Even If You’re “Just Using Pandas”)

Employers don’t just want someone who can write Python. They want someone who can:

- Take messy inputs and produce reliable outputs

- Make data consistent enough to join, aggregate, and trust

- Catch problems early instead of discovering them in a broken dashboard

- Explain what changed and why

Pandas is not just analysis. Used correctly, it’s a mini data engineering toolkit.

Leave a comment